A version of this post was originally distributed in Votebeat’s weekly newsletter. Sign up here.

A newly revealed text message about Christy McCormick, a commissioner and past chair of the Election Assistance Commission, raised eyebrows among election observers this week. The exchange between two Arizona state senators notes that McCormick agreed to let them use her name in their press release announcing the “audit” Cyber Ninjas would conduct, to be sent out in late January, though it was apparently never released.

In a message to Arizona Senate President Karen Fann, state Sen. Warren Petersen writes, “McCormick says she’ll be in our press release too.”

“So won’t she be in deep dodo [sic] for saying this public[ly]?” Fann asked. “Nope, it’s a fact,” Petersen responded.

A screenshot of the message came in a document dump given to American Oversight, as part of the organization’s lawsuit against Senate Republicans in pursuit of more transparency into Cyber Ninjas’ contract and work. The text messages weren’t clear about McCormick’s role in the press release or whether it would signal her support for the audit, and McCormick has provided no public explanation, so I asked for one. McCormick offered a statement: “Commissioners respond to requests from state officials on a weekly if not daily basis. As I do with any state official, I relayed the factual and publicly available information that EAC labs are not accredited by the EAC to perform the type of work that Arizona was seeking to do. The EAC did not track nor see a press release in this instance, and what gets published is not always within our control.”

Those who have talked to McCormick about this tell me they believe her: She was asked by Arizona officials if the EAC-accredited labs could do the kind of audit Fann and Petersen sought, and McCormick — not knowing what kind of audit they even wanted — told them it was not the EAC’s function. Because the press release wasn’t issued and Arizona Republicans haven’t been transparent about the decision-making behind the audit, we’ll probably never know the details of the exchange, but McCormick’s explanation seems plausible. It’s not helped by the fact that apparently no one else at the EAC knew McCormick had taken such a call, or green-lighted her name for a press release. (It’s not clear from McCormick’s statement if she even knew if a press release was in the works, or expressly gave permission.)

The explanation would be believable and entirely reasonable coming from most other election officials. But McCormick has a years-long history of working behind the scenes at cross purposes with the EAC’s goal of strengthening elections, as revealed in text messages or emails made public in lawsuits or by records requests. Let’s review the evidence.

After 2016, McCormick began to surprise those who had known her work by actively resisting the finding that Russia had interfered in the November election. She repeatedly attempted to convince state election officials it was nonsense. She did so at conferences, she did so by email. “It is my opinion that the entire thing is complete BS,” McCormick wrote to her fellow EAC commissioners and the director of an election association on Dec. 30, 2016. “It sickens me that this administration appears to be creating false intelligence narratives to bolster whatever their agenda is.” She forwarded the full chain to Georgia Secretary of State (now governor) Brian Kemp. “I am appalled by what I am seeing,” she said. He replied to her, calling it “unreal.”

She didn’t keep it to election officials — she made these claims publicly and with no regard for the facts. In a blog post she published on the EAC’s website in January 2017, McCormick wrote that the claims were “deceptive propaganda perpetrated on the American public” by the outgoing Obama administration. She would not publicly correct this assertion until 2019.

And it wasn’t just words: I reported in 2018 that in the months after the 2016 election McCormick passed up multiple opportunities to hear classified briefings on the issue, essentially lying down on the job as an EAC commissioner. Neil Jenkins, who worked with DHS at the time, told me that she rarely came to meetings, and when she did was actively hostile to the information presented.

In 2017, McCormick shocked the election world by willingly participating in Trump’s “voter fraud commission,” the drama of which I covered from start to finish. Emails released (also by American Oversight) show that McCormick worked behind the scenes with Republican commissioners Hans Von Spakovsky and J. Christian Adams to find right-leaning staff members to employ. She recommended one statistician, and said she was “pretty confident that he is a conservative (and a Christian too).” When I spoke to her at the voter fraud commission’s first meeting in 2017 at the White House, she told me she’d joined the commission because she’d seen voter fraud with her own eyes. She didn’t elaborate.

She usually doesn’t. Her statement to me this week was the first time she’d responded to any of my questions since that conversation in 2017. Dozens of emails, texts, and calls to her have gone unanswered. I even sent a ProPublica colleague to ask her questions once, hoping a different reporter would have more luck. She yelled at him. But it’s not just me, apparently: McCormick has had multiple opportunities to explain herself to others who have questioned her actions—but has chosen not to. In July 2018, Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Oregon, asked her in a committee hearing to offer some explanation of her Russia-interference doubts, saying, “I can’t for the life of me figure out why the No. 2 official at the Election Assistance Commission is dismissing the analysis of the administration’s intelligence experts.”

As my previous reporting found, McCormick was responsible for the removal of fellow commissioner Matt Masterson in 2018. She and Von Spakovsky approached then Speaker of the House Paul Ryan’s staff directly, asking for Masterson to be replaced, and Ryan did it. Even though officials who were unhappy about Masterson’s ouster demanded answers about her alleged involvement, McCormick didn’t provide them.

And in the run-up to the 2020 election, McCormick kept these antics up. Records requests from American Oversight yielded documents that showed McCormick stayed in regular contact with objectively partisan entities during 2020. She also went on True the Vote’s podcast and did not correct multiple false assertions by the host about the validity and security of vote by mail. Instead, she amplified them, offering baseless concerns of her own: She said voters would be mailed ballots regardless of “whether we know if they’ve died or not,” and that the “security involved is a lot less with a vote by mail scheme than it is with an absentee ballot scheme.” Almost any election official from either party will tell you those claims are not true. One official, quoted in my piece, called it “bollocks.”

And so, while McCormick’s explanation of her exchange with Petersen might be plausible, her history of causing friction against the EAC’s interests gives people plenty of reasons to be skeptical. Even if she did nothing wrong in this specific instance, there’s obvious reason to be concerned that she never told her EAC colleagues that she’d had a conversation with a state senator hellbent on investigating an already-audited and certified election.

The kerfuffle over McCormick is happening during an otherwise bright spot for the EAC. The agency has hired well-respected new staff and has begun to put out useful information for elected officials of the type that they have been requesting for years. The agency got a funding boost last year, affording it more opportunities to provide the services that election officials need. And, if federal legislation to boost election funding passes, the EAC will be completely responsible for distributing it. Public attention on another episode in McCormick’s pattern of controversies threatens to overshadow that recent progress.

Back Then

The EAC has been struggling from the beginning. It was established by the Help America Vote Act of 2002, and the law required all four commissioners to be selected and in place by February 2003. They weren’t actually confirmed until December of that year. In early 2004, the agency still had absolutely no budget and no office. The four commissioners would occasionally meet at a Starbucks. The Voluntary Voting System Guidelines were established in 2005, and then the agency sort of puttered out. The agency’s first commissioner resigned that year, saying the government’s dedication to the agency was lacking. By this point, U.S. Rep. Gregg Harper of Mississippi had zeroed in on the agency, proposing multiple bills to disband it. He failed at that, but was successful at reducing the agency’s budget to — in federal budget terms — next to nothing. Two years ago, the agency began to receive funding boosts again.

In Other Voting News

- The Republican majority in the Michigan Senate passed a bill to add requirements to absentee voting and make voter ID laws more strict. In addition to requiring a valid form of identification, the bill also prevents election workers from sending out absentee ballots unless a voter specifically requests one. The bill, which Gov. Gretchen Whitmer is certain to veto, is closely aligned with a ballot petition that “Republicans plan to adopt and pass through a quirk in Michigan law that would allow them to evade a Whitmer veto,” Bridge Michigan reports.

- AZ Mirror’s Jeremy Duda has a great explainer on all of the ways Arizona “audit” “expert” Shiva Ayyadurai botched claims about vote by mail and other election procedures in his report and testimony before the Senate. “Ayyadurai appeared to have absolutely no knowledge of Maricopa County policies and procedures regarding the early ballot envelopes and signature verification,” writes Duda. “That shortcoming would be a consistent theme as he presented his findings as part of the so-called audit of the election in Maricopa County, portraying commonplace occurrences and standard procedures as potentially suspicious.” Maricopa County likewise issued its own official rebuttal this week to the claims in each part of the Senate’s election review.

- One of Wisconsin’s election investigations — which is expected to cost almost $700,000 — is underway. Milwaukee announced it would comply with the investigator’s subpoena, which will include thousands of documents and information on every ballot cast. The documents are due on Oct. 22. Officials in Milwaukee have sought clarification on the scope of the documents at issue, the specifics for which officials say are “very broad.”

- The Pennsylvania election review is off to a pretty slow start. Senate Republicans say they won’t hire a contractor to begin the process until a judge reviews a current legal hurdle: Republicans subpoenaed information on every registered voter in the state, and Democrats sued to block the release of it. While the deadline for handing over the data was Oct. 1, the secretary of state has not provided it.

- Idaho will be sending Mike Lindell, the MyPillow CEO, a bill for $6,500 for audits in three counties after Lindell claimed mass fraud. In a widely circulated memo called “The Big Lie,” Lindell asserted that electronic votes in every Idaho county had been manipulated. “Why not try and get Lindell to reimburse the state for having to refute his false claim?” Idaho Chief Deputy Secretary of State Chad Houck told the Statesman.

- The Lexington County, South Carolina, Republican Party has passed a resolution calling for an audit of the county’s election results, even though Trump won the county handily. Even the county’s state senator, a Republican, is confused and says such an audit would be a waste of taxpayer money and government time.

- With all these partisan audits and third-party investigations, it’s hard to take note when an official audit, performed using best practices, makes the news. The Washington Post has a great analysis about the ways New Hampshire’s recent audit should serve as a model for the rest of the country.

- The Department of Justice has prevented ex-Trump officials from talking about allegations of 2020 voter fraud as part of their testimony during the investigation into the Jan. 6 insurrection. Politico reports that Biden administration attorneys repeatedly told Senate aides that the topic was outside the scope of the investigation, blocking the answers.

- New Jersey is facing a massive poll worker shortage and has upped pay from $200 to $300 for workers who serve at the polls for a full day on Nov. 2, the day of the state’s election. “Early voting coupled with an increase in pay for poll workers, is critical to maintain the accessibility, security, and safety of this upcoming election,” said Gov. Phil Murphy.

Now Featuring Francois

Readers, we would like to introduce our fall intern, Francois Barrilleaux! He is a student at the University of Pennsylvania, studying political science and survey research. He’ll be helping us flex our data muscles this semester and contributing to the newsletter. Look for his work each week in this space.

Francois also will be managing our featured hobbyists (please submit your nominations), so in that spirit, here is Francois’ hobby, in his own words:

Hello! Like many of the hobbyists featured in this newsletter, I play in a band. Queen of Sheba consists of me and some college friends. I play the keyboard and occasionally sing. I’ve been playing piano for almost 10 years, but before this I’d never played with other people — it’s been a learning experience. The band is ever-changing — we continue to add people, playing different instruments whenever they have time. Right now we have piano, guitar, bass, drums, vocals and saxophone.

And since we ask all of you to tell us how your hobby has made you think differently about elections, it’s only fair I should, too: Playing music in a band has made me think more about how to make other people’s work shine. A big part of playing music with other people is knowing when to solo and when to support someone else who is playing. I think that’s important in any type of work you do, including the work I do related to elections.

But I am really here to tell you about a cool infographic. Every couple of weeks, I’ll highlight a fun piece of data or infographic that I think is relevant to today’s election administration ~discourse.~

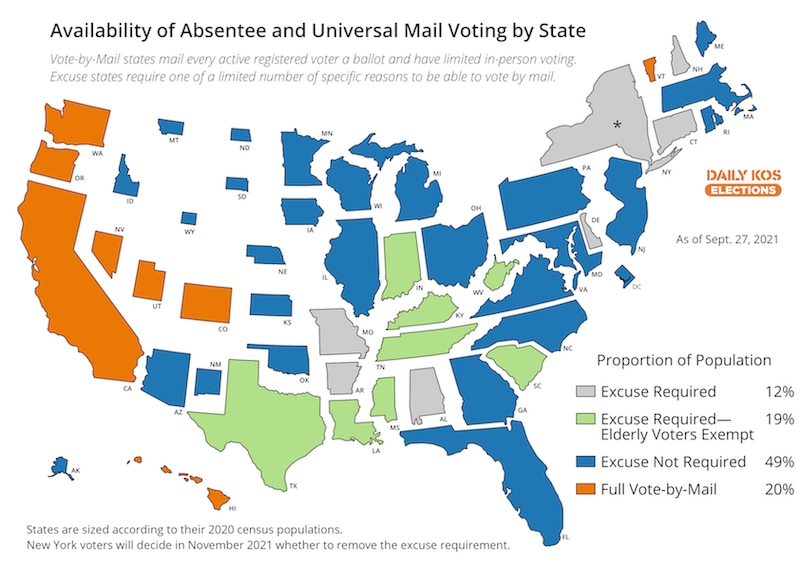

This week I bring you a map I discovered from Daily Kos, showing the current status of vote by mail availability, delineated geographically and as proportions of the U.S. population:

California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill Sept. 27 ensuring that mail ballots will be sent to voters in all future elections. California joins many of its Western neighbors — including Hawaii, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, and others — in making vote-by-mail central to the conduct of its elections. The map shows how the accessibility of vote-by-mail continues to vary dramatically depending upon where you live. And using the map’s population breakdowns, you can see voting by mail is relatively accessible to 69 percent of Americans—more than two-thirds of us. (Note that’s total population, a rough stand-in for the voting-eligible population.) So the policies already exist to quickly make this mode of voting the norm. But because the pandemic brought vote-by-mail into the national spotlight and sparked furious partisan disagreement, further changes to state laws could change that state of play.

Are you a political scientist or election-data guru with an interesting finding you’d like me to feature here? Email me at my fancy Votebeat address!